It's the economy!

Part 1 of 6

A long time ago, a colleague and I were working in a very poor neighborhood in Chicago.

At one point, he turned to me and said, “There aren’t many problems here that wouldn’t be helped greatly if folks had more money.”

In our comprehensive community development work we say everything is important. Or maybe, all of the right things, for the given community, are important.

In the scores of neighborhoods I have worked with across the country, the ingredients are all the same array of program/issue areas which include work around housing, education, safety, job readiness, health, financial literacy, and many, many more.

Yes, the ingredients are the same. But, in each and every neighborhood, the recipe is different. Finding the right mix of strategic work for these people, in this place, at this time is the key to success. That is what quality-of-life planning is really all about.

But, now, it is time for me to make a little confession. We say all of the program areas are equally important, but I don’t think that is really true.

I think there is one program area that that is more strategic --- and more important --- because when done well it can enable everything else.

I am speaking of economic development.

In most places --- like that very poor neighborhood in Chicago --- the critical question to answer is: How can folks get more money?

Part 2 of 6

How can folks get more money?

That's a question we haven’t answered well in most places. In fact, the things we usually call “economic development” projects many times don’t really help to “develop the economy.”

Here’s an example:

Many years ago, as a CDC director I worked long and hard to develop a supermarket grocery store which we located in a very blighted commercial district.

It was a difficult project that taxed all of our capabilities at the time. The development process even fell victim to political corruption --- hard to believe in 1983-era Chicago, I know --- and hardball confrontational organizing tactics had to be deployed.

Despite development difficulties, the store has been operating since 1985 selling groceries and fresh meat, fish and produce in a former food desert. Also, since our CDC owned 1/3 of the real estate, we received about $30,000 or more a year from the net rent.

Over the years, when I would conduct a tour of the neighborhood, the bus would roll up to the supermarket, and I would explain the project. Then, some version of the following conversation would occur:

Capraro: . . . and so that is the story, or should I say saga, of why and how we built the supermarket.

Tour members: What a wonderful economic development example.

Capraro: No, it’s not.

Tour members: But, it is business development.

Capraro: Yes, it is that. But not all business development grows the economy.

By this time everyone on the bus would look pretty confused. Some who, at the time, were working to bring to bring a grocery to their community and calling it economic development would even get angry. So the conversation would continue:

Capraro: To develop (grow) an economy you have to EXPORT something (like goods, services, labor, entertainment) in exchange for money. A grocery store does just the opposite it IMPORTS product in exchange for local money. Think of it this way, our community suffered from a “trade deficit” which we ENHANCED by building the super market.

Tour members: But what about the jobs in the supermarket? Aren’t they bring money into the community?

Capraro: Well, technically, no. It is true that, if the folks who work at the supermarket live in the community, they will be taking home paychecks. However, the source of the money used to make the payroll is from the revenue generated by the grocery sales, money which came from our community to begin with.

So through local employment we are recycling local money back into the local economy. But that is not as powerful a contributor to economic growth (economic development) as bringing new money into the local economy.

Economists call this “import substitution.” Import substitution helps to stop the bleeding of wealth out of a community as residents go elsewhere to shop. But, again, it does little to contribute to economic growth.

Tour members: So why did you go through all of the trouble to create this supermarket?

Capraro: Two reasons:

1. People really need groceries. (If this were the only reason, it would be worth doing.)

2. This commercial corridor was terrible, populated with vacant and abandoned structures, some of which were fire-gutted. The grocery store development served as commercial revitalization anchor.

After we developed it, all of these other smaller surrounding retail companies wanted to locate their shops as close to the anchor as possible.

We didn’t build the grocery store to bring money into people’s homes. It won’t produce a large volume of mortgage-paying, family-raising income, and we’re not counting on it to increase home ownership potential much.

---

So, that supermarket isn't a good example of economic development.

And I still haven’t answered the key question: How do we work so that folks can get more money?

Part 3 of 6

Early in my career I read two books by the great urban thought leader, Jane Jacobs: “The Economy of Cities” and “The Life and Death of Great American Cities.” These are seminal works that guide one to understanding just how important trade, and more specifically, export is to any given place and the people who live there.

However, I experienced my real on-the-ground learning about economic development from pizza and ice cream.

Pizza, ice cream --- and exporting

In the late 1970’s two brothers, Efren and Joseph (Giuseppe) Boglio opened a pizza parlor in our neighborhood. It was just a hole-in-the-wall sort of place with a few used Formica tables. Every night you could go there and find the Boglio brothers standing behind the counter, with spaghetti sauce (or in Italian “sugo”) on their long white aprons, making pizza.

Oh, what a pizza!

From a family recipe given to them by their mother, it was a real “pie,” about four inches tall, crusted on both the top and bottom, with nothing but Italian goodness in between, and a layer of sugo and cheese on top. Folks from the community would flock to this little pizzeria because, once you tasted its pizza. you couldn’t help but dream about it.

So you might say: “Neighborhood folks eating pizza. Import substitution maybe, but certainly not full-fledged economic development.”

But, wait, there’s more.

To the moon

In 1979 Chicago magazine held a secret pizza contest. They commissioned food critics to secretly eat pizza at scores of Chicago’s neighborhood pizzerias, judged the results, and then declared the winner to serve the Best Pizza in Chicago.

I can remember the cover of the magazine. It had that famous picture of Astronaut Alan Shepard planting the United States flag on the moon, but, instead of standing on the moon, he was planting the flag on a pizza, and Old Glory was replaced with the four-star Chicago Flag.

I was amazed when I spotted on the cover, right under the picture of the flag, the name of Efren and Giuseppe’s mother --- you see they had named their little pizzeria “Giordano’s” in honor of their mom, Giordano Boglio.

After winning the contest, Giordano’s became a powerful culinary destination. For the first six months, each evening, hundreds of patrons would travel to our community for an ethnic eating adventure. There were evenings when the restaurant turned away up to one hundred people because there was no room.

Efren and Giuseppe were frantic when they contacted our CDC. They needed more space --- and they needed it fast.

At the time we had just finished the rehabilitation of a three-story commercial building that had been ravaged by a terrible fire. Within three months, Giordano’s was in this new space, serving lots of customers, with an increased complement of cooks, bus boys/girls and wait staff.

The Chicago Magazine award had transformed Giordano’s retail trade. Originally serving our community market, the award generated an appeal for their product throughout the Chicago region. Overnight, their base of customers from outside of the community grew to a level that dwarfed the volume of local consumers.

Giordano’s (which has had its financial problems in recent months) was now an exporter, transporting their food outside the community --- mostly in people’s stomachs --- and importing external cash, generating a pizza trade surplus.

Collateral benefits

There were collateral benefits for the neighborhood as well.

As folks traveled to our newly famous pizzeria, they noticed other unique and interesting local retail offerings, and started to patronize those businesses. There are several examples, but I’ll mention one here.

During the year that followed Giordano’s discovery, a new consumer pattern developed. After dining at Giordano’s customers would travel to another local retailer, a short distance from Giordano’s, on the way to the expressway, to partake of desert.

This was a small family owned candy store, that also sold hand-made/hand-dipped ice cream bars --- Dove Candies. Just inside the front door of the Dove Candy shop was a white freezer with sliding glass doors. Inside the freezer where stacks of Dove’s Ice Cream Bars, or as we now know them, DoveBars.

Each Ice Cream Bar was wrapped in plain white paper, and the flavor was hand-stamped on the popsicle stick. Dove Bars were so thick that you could stand them upside down on their head --- it’s where the saying “The DoveBar stands alone” comes from.

Total cost for a 1980’s Dove Bar -- 35 cents. Like Giordano’s, Dove Candies was now exporting food product

Several other businesses also benefitted from this new external market. Among them where bakeries, ethnic grocers, other ethnic restaurants, clothiers, and a hobby shop.

And, as sales went up, so did the need for space, employees, and supplies.

Part 4 of 6

Last time, I told the story of the success that a neighborhood pizzeria, Giordano's, had in exporting its product --- and importing money to the community.

For me, it was an economic development epiphany.

In 1980 I was 30 years old and had been a CDC Executive Director for four years. I had consumed the works of Jane Jacobs with fervor. But I didn’t really understand how to put her ideas into practice until the experience with Giordano’s literally fell into our lap.

Now, we understood what an economic development project looked like and what it could produce. So, we set out to generate them.

Although the Giordano’s success was great, it lacked one feature that we needed as community developers --- scale.

In our quest, we set out to find work that could create/sustain local export opportunity and capacity on a much larger scale so more of the folks in our community would have the opportunity to “get more money.”

So, let me tell you about one such projects.

Rapid transit economic development

In 1980, Joel Bookman had my job at the opposite end of Chicago. Joel was the Executive Director of the Lawrence Avenue Development Corporation.

In those days Joel, his predecessor Scott Berman and I would visit and talk often, sharing and stealing ideas from each other. One day, Scott was “instructing” as the three of us were walking in their community at the intersection of Lawrence and Kimball.

I was amazed when Scott pointed out the el station (el for elevated subway line) and the thousands of folks from his neighborhood passed through its doors on their daily commute. Scott was using these numbers to demonstrate the depth of the market for the surrounding retail corridor. As he talked, I watched endless waves of people streaming though the train station. I was impressed.

It is a long drive from the Northwest side of Chicago to the Southwest side. In good traffic, it takes nearly an hour. I didn't have good traffic that day. As I made my trek back home, inching along in my car, I kept thinking about that train station. As Scott said, it did deliver consumers to the commercial street, but another notion was developing as I thought more deeply about it.

The el passengers were folks from Scott’s neighborhood. They were taking trains to commute to and from their jobs in downtown Chicago.

Conclusion: The existence of the el enabled Scott’s neighborhood to export labor to downtown Chicago in exchange for wages that workers brought back to the community. And the numbers of el travelers indicated that this was happening at a large scale.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the amount of office space in downtown Chicago grew by 150%, generating more than 200,000 new jobs. At the same time, neighborhood blue-collar jobs were disappearing as Chicago’s economy transformed from manufacturing to service.

For labor, downtown represented a major new growth opportunity. In those days hardly anybody actually lived downtown so those jobs would be occupied by commuters. But to take advantage of this opportunity, you had to be able to easily commute.

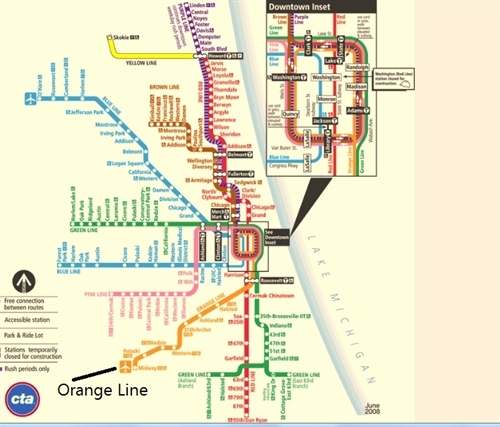

Even though Scott’s neighborhood and our community were equidistant from downtown, because of the el, Scott’s commute time was 30 minutes on one train. Ours was 70 minutes on a complicated array of bus routes.

And, while bad weather didn’t affect the train much --- well, buses were another story.

An el of a question

How to get an el line?

That was the question. I obsessed over it. We asked everyone. We talked to the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) and the Regional Transit Authority (RTA). We talked to our city, state, and federal elected officials. We talked to the City of Chicago.

It was at the City of Chicago Department of Transportation that we got our first glimmer of hope. They revealed that they had a concept for a new el line that would connect Midway Airport to downtown --- but the work had been shelved because of the lack of a capital allocation to build the line.

There was an idea for a line, planned by city transportation experts, but no money to actually build it.

So, we kept meeting with folks, using all of the relationships we had generated throughout our time in business to advocate for this idea.

One such meeting was with our state representative, and, together, we had a brainstorm.

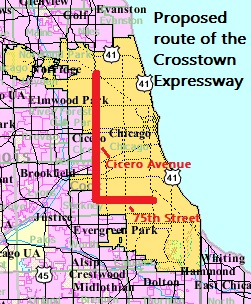

During late 1960s, there was a plan to build the Crosstown Expressway, a mid-city beltway that would cut a crescent through Chicago’s bungalow belt.

The Crosstown Expressway was reviled in most, if not all, of

the neighborhoods it would traverse and became the subject of huge protest actions. It was officially scrapped in 1972, but not before it had received a sizable federal allocation to pay for its construction. These unspent funds were still held in reserve by the former Federal Urban Mass Transit Authority (UMTA).

Armed with the city’s idea and a potential funding source, we organized. By this time. Harold Washington had been elected Chicago’s mayor. As it turned out, City department heads were now wholly behind this new train line and had already identified the unused expressway funds as the means toward that end.

We partnered with the city, our elected officials, and several other organizations. It was a perfect coalition --- we could deliver citizen/neighborhood support behind stalwart, forward-thinking government leadership.

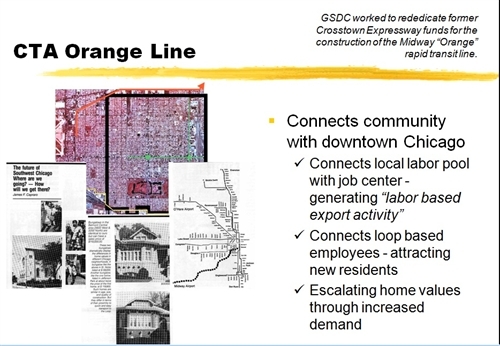

Ultimately we were successful, and the Crosstown Expressway funds were reallocated to build the new el line. Start to finish, this campaign took almost a decade to produce results. Construction started on the $510 million line in 1985, and, in October, 1993, the Orange Line opened, connecting Midway airport and our Southwest Side neighborhood to downtown Chicago.

Within two years of its opening the Orange Line became one of the heaviest traveled CTA routes.

Benefits and lessons

Our neighborhood received a double benefit. First, our folks had better access to downtown jobs,

increasing our neighborhood's ability to export labor and import paychecks. Second, folks who already were working downtown discovered our community as an affordable and desirable community to move to. This new demand stabilized a local mixed-income economy, importing even more paychecks, and deepening the pool of local spending power to support local retailers.

We didn’t cause the Orange Line. But we did encourage it, and participated in creating the political momentum to see its development. Once built, we sure took advantage of its benefits.

There were two large lessons for me.

(1) If you can discover the economic forces that are at play in your region, find the growth sectors --- in this case, service economy downtown office jobs –-- and create a way to link to them. Then, you'll deliver economic development benefits, at scale.

(2) A community development corporation or a neighborhood organization can become an appreciated team player --- a partner, a go-to organization --- for the government, elected officials and, as I later learned, the private sector. And it can play a real and critical role in getting big things done.

Part 5 of 6

Here’s a story that demonstrates just how potent a CDC can be as an economic development actor when:

(1) There is a good understanding of this export-driven economic development strategy.

(2) You are seeking to operate at a scale that can really make a difference for your community.

(3) You have earned the status as a trusted, capable partner with important government leaders, elected officials, and (as this story will illustrate) the private sector.

(Notice I didn’t include philanthropy in the above list.)

The call

In 1992, I was sitting at my desk when the telephone rang. The caller was Valerie Jarrett, now Senior Advisor to President Barack Obama. At that time, she was the Commissioner of Chicago’s Department of Planning & Economic Development. She was calling us to enlist us in some very important work.

Valerie had been contacted by the law firm Skadden, Arps. Skadden is noted for their robust portfolio of major corporate clients.

They were calling on behalf of the tobacco company, R. J. Reynolds. R. J. Reynolds owned Nabisco, the household name in baked delights, such as Chips Ahoy, Lorna Doone, Fig Newton, Nutter Butter, Premium Saltines, and their flagship product, Oreo cookies.

World's largest bakery

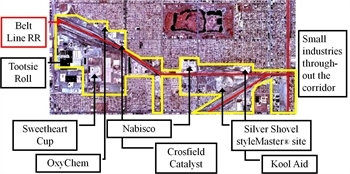

One of Nabisco’s facilities — the world’s largest bakery — had been operating in our Chicago neighborhood since the early 1950s.

The systems and technology in the plant were dated and inefficient. Newer modern bakeries could produce the same product at a fraction of the cost. The company was deciding about the future of this bakery.

Its options were: (a) close the plant and move the operation to Mexico, (b) close the plant, break apart its components and move them to several smaller facilities, (c) a combination of options a and b, and (d) invest in modernizing the plant and training its workforce to use the new equipment/systems.

Now, romanticized community development lore would have you believe that we were such a great community organization, with our “ear so close to the ground,” that, through local relationships, we learned of this dilemma ahead of time and put together a strategy to force Nabisco, and the city to act in our favor.

WRONG!! The Nabisco plant manager didn’t even know that the parent company was considering this.

The potential catastrophe

Closure of this plant would have been a catastrophe for us. The world’s largest bakery was our community’s largest manufacturing employer (1,800 union jobs), and our largest exporter. The Oreo baking line alone produces 22 million cookies each and every day.

And to bake cookies Nabisco needs to consume a lot of stuff. Sure, they need chocolate, flour, sugar, etc., almost all of which comes from outside our community and arrives by train.

But they also need to purchase roofing, electricity, gas, pallets, ink, paper, cardboard, aprons, hairnets, asphalt, labor (of course) and many other things, all of which can be supplied locally.

This supply chain provides for a different kind of ECO-SYSTEM – an ECOnomic-SYSTEM. By selling cookies all over the world, Nabisco brings large streams of cash into our neighborhood and city. The more that local suppliers positioned themselves as vendors to Nabisco in that supply chain, the greater the cash could be captured by our neighborhood, city and region.

The only communication about the potentially ominous Nabisco decision was that call from m Skadden, Arps to Valerie Jarrett.

So Valerie and members of her city department went to work.

And she called us.

As we entered the conversation, I learned that Nabisco plant modernization estimates ran upward of $300 million in capital equipment-upgrade expenses. And a large, undetermined, collateral workforce training expense would also be incurred as incumbent workers would have to become proficient with new technology.

A further challenge would be the task of undertaking this investment within the current plant while not hampering production --– a problem that didn’t exist if the plant were moved.

The city was already moving rapidly on the creation of a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district to subsidize the capital costs, and the expansion of a nearby Enterprise Zone to write down with the training cost.

The community organization's role

Valerie and I envisioned that our neighborhood organization could help in two strategic ways:

Community support: At the time, there was mounting public criticism in Chicago concerning the use of TIF district financing. Some previous projects (before Valerie’s tenure) had failed to produce their intended results, and some others were established despite the fact that developers had proffered a disingenuous case for their necessity. We could provide community support for the corporate subsidies that the government needed to provide, demonstrating that they were bona fide.

Community context: At their headquarters, the top R. J. Reynolds/Nabisco officials had asked a strategic question about the invest-in-place option, and the city turned to us to help to provide the answer. The question was: “If we were going to invest this large amount of capital in our bakery, located in this Chicago community, we need to know how the community is doing, and what its future looks like?” Nobody could prepare a better answer to this question that we could.

We and the City worked long and hard together, designing a TIF that would subsidize the capital investment while also crafting a well-supported case for the establishment of the TIF. We also worked to expand the boundaries of a nearby Illinois Enterprise Zone as a way to create eligibility for Illinois employee training subsides.

As the development package came together, R. J. Reynolds/Nabisco sent a corporate team from their Parsippany, NJ headquarters to review the deal.

We organized a neighborhood tour for this group which included private meetings with several local companies, such as Sweetheart (now Solo) cup, Sears, Toyota, Jewel Foods and others. At these sessions, local business leaders disclosed their sales/profitability/trending data, market info, and employee/hiring experience.

The decision

At the end of the tour, the leader of the corporate team declared: “This neighborhood isn’t dying! It’s being reborn! I feel very comfortable with any future investment we might make here.”

When the establishment of the TIF district and the expansion of the Enterprise Zone District came up for public hearings, we delivered busloads of community supporters, and testified as well.

In late 1994, we were rewarded with a positive decision by Nabisco which subsequently invested over $300 million in the bakery.

It was a true win-win proposition. We kept 1,800 union jobs in our community, and Nabisco greatly increased its productivity.

A more profound victory was the fact that we not only kept our community’s largest manufacturing exporter in place, but we helped it to increase its export capacity.

We were able to grow our community’s trade surplus and increase the cash flowing into the community through Nabisco. This created greater opportunity to capture some of that cash stream, not just through employment, but also by creating opportunities for local companies to enter the Nabisco supply chain.

These are the kind of income opportunities — both employment and entrepreneurial — that you can rely on to both pay a home mortgage and raise a family. More money was flowing through the neighborhood, and more local people could get at it.

Part 6 of 6

You can see from the examples I’ve cited in the earlier postings in this blog series that it really is possible to produce results that create opportunities for constituents of our target communities to “get more money.”

When we do this, we are creating healthy mixed-income neighborhoods by increasing the incomes of folks who are participating in these new opportunities.

Housing becomes more affordable, and so do groceries, clothing, tuition, health care, and vacations.

When a community’ export capability grows — in a way that allows the indigenous population to participate in that economy — the neighborhood can move from deficit to surplus, from disadvantaged to opportunity-laden.

Accomplishing this will create sustainable communities, and perhaps in some places might even move beyond sustainable to thriving.

Around the nation

As I travel around the country, working in scores of neighborhoods for National LISC, I’ve seen local work that, if nurtured correctly, could yield significant export opportunities.

--- The Heritage Center in the Duluth, MN, neighborhoods of Lincoln Park and West Duluth has become a Minnesota-wide mecca for amateur hockey. Recently analyzed and assisted by Metro Edge, the Heritage Center is a nascent destination point for a hockey/sports/tourism economy.

Duluth Heritage Sports Center, Patrick T. Reardon

--- In Houston, TX, and St. Paul, MN, Sustainable Community neighborhoods are positioning to export labor to distant job markets when planned surface rail transportation systems are put in place.

--- In Greenville, MS, three components — the annual Delta Blues Festival; the birthplace/childhood home of B.B. King in nearby Indianola; and the “Crossroads” in nearby Clarksdale, of Robert Johnson fame — can anchor a uniquely African American cultural /entertainment destination point.

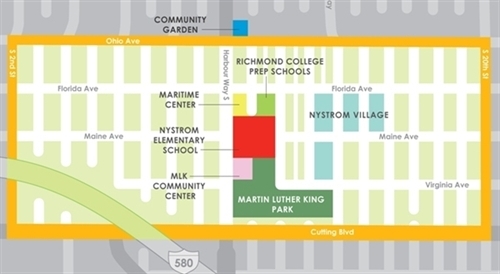

--- The Nystrom neighborhood in Richmond, CA, long a food desert, is creating a new market for the produce grown in the surrounding, lush, farmland of Contra Costa county. As this demonstration project matures and becomes seasoned, it could serve as a model for expansion to other inner-city food deserts in the San Francisco Bay area, and beyond.

--- And finally, to come full circle, the northwest Chicago neighborhood where I walked so many years ago with Joel Bookman and Scott Berman is another example. Sure, it still exports tens of thousands of workers to downtown Chicago every day. But also, there is now evidence that this community is incubating the next generation of Giordano's-type businesses. Thanks to the legacy of retail revitalization prowess created by Scott and Joel and the current complement of very capable staff who have picked up their mantle, these neighborhoods have become a destination point for fine ethnic cuisine and cultural experiences of all sorts.

Albany Park

Focus — and re-focus

Over the last forty years, the community development industry has focused the lion’s share of its effort on affordable housing. (I could tell you why, but that is best left for another series of blog posts.)

We have developed elaborate and complex ways to design, package, finance, construct, market, and manage affordable housing units. But this over-concentration has come at the expense of other, perhaps more vital, program areas.

If we can concentrate our thinking and develop ways to both envision and support the growth of export capacity and community economies, we will harvest a bumper crop of sustainability.

Hmm. Sounds like a job for the Institute for Comprehensive Community Development.